A staircase comes to an abrupt halt near the Sheraton Waikiki in Honolulu. All photos by Marco Garcia for Politico Magazine

Waikiki’s beaches, hotels, boutiques and restaurants are increasingly threatened by rising sea levels. Map: Sean McMinn / Politico

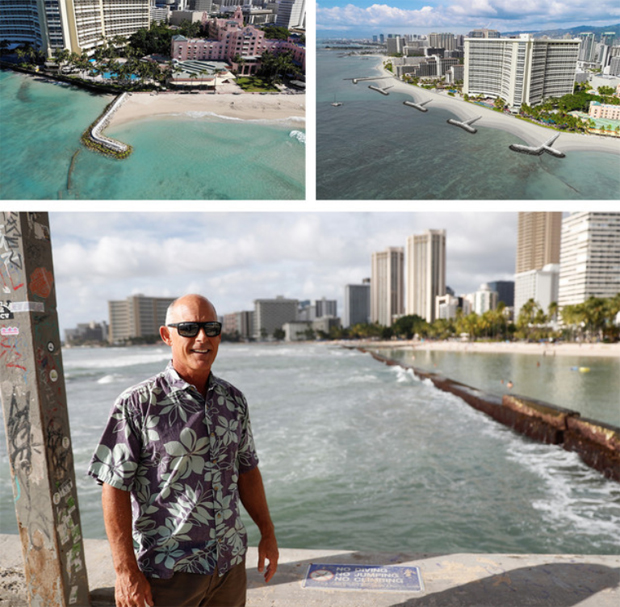

Dolan Eversole of the Waikiki Special Improvement Association oversaw construction of an L-shaped groin, top left, near the Royal Hawaiian that “holds the beach together”. Nearby, his group plans to build four new T-shaped groins, modeled top right.

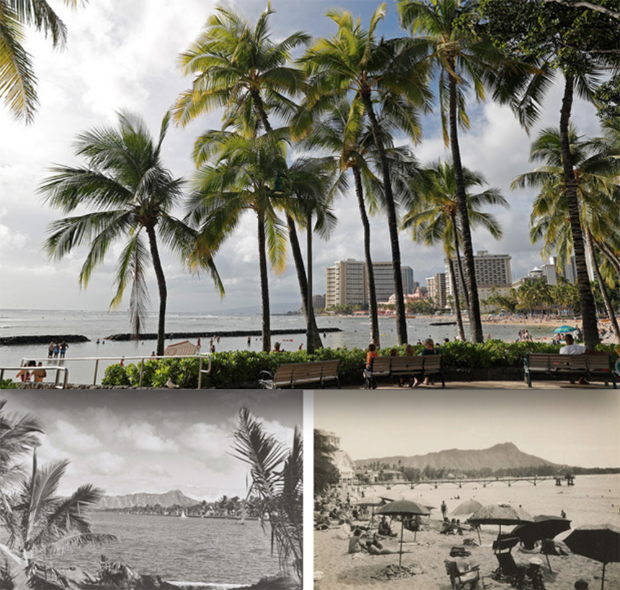

The completion of the Ala Wai Canal (left) in the late 1920s allowed for the construction of more houses and hotels on Waikiki, leading to more tourist activity (right). | The Hawaii State Archives

Keone Downing, pictured inside his surf shop, has become one of Waikiki’s most prominent voices arguing that current climate adaptation efforts favor hotels over locals, including surfers.

29 January 22

HONOLULU - Waikiki might be one of the most famous beaches in the world, a synonym for surfing and sun-soaked vacations that draw millions of people annually. But for years, Honolulu and the State of Hawaii have been reckoning with a very uncomfortable fact: The beach is vanishing.

Just below the infinity pool at the Sheraton Waikiki, an advancing shoreline claimed a walkway and set of concrete stairs, which now dangle above the water. At the Outrigger Reef hotel, ocean water laps directly against the wall of the new Monkeypod Kitchen restaurant, still under renovation.

Like many places buffeted by the ocean, Waikiki has swung into action — to a point. The hotels along the beach are worth north of a billion dollars, and to preserve that investment, hotel owners and other businesses fund the Waikiki Beach Special Improvement District Association as a kind of coastline-repair department. Near the pink, 94-year-old Royal Hawaiian hotel, the association (in partnership with the state) recently built a $1.8 million groin — an L-shaped finger of rock and concrete that juts into the water and holds sand in place — in addition to widening the beach by 30 feet with 20,000 cubic yards of sand vacuumed up from the bottom of the sea.

The group’s next phase of work calls for more of the same: Spending at least $50 million, much of it likely from state and perhaps federal funding, on four more groins and the construction of an entirely new beach in the area fronting the Sheraton, Outrigger Reef and Halekulani hotels.

"People might be surprised by how much of a man-made beach this is,” says Dolan Eversole, a 51-year-old coastal geologist who represents the Special Improvement District Association. On a hot, sunny morning in December, Eversole stood on a narrow walkway above Waikiki’s turquoise waters, motioning toward the existing groin as a steady stream of people emerged from the Royal Hawaiian and onto the sand. “It literally collects the sand and holds the beach together.”

'Place of Spouting Water'

But reengineering the beach in the future is only going to get harder. Studies and modeling show that the combination of thermal expansion and melting polar ice will cause a global, 3.2-foot sea level increase sometime between 2050 and 2100, resulting in twice as much coastal erosion in Hawaii as there would be otherwise. When this happens, today’s projects will seem futile. “We’re buying time,” Eversole admits. “The beach won’t be here forever.”

Neither will the rest of Waikiki’s 1.5 square miles beyond the beach, at least not in their current form. As the ocean expands, water is expected to seep into Honolulu’s porous limestone geology, nudging up the water table and eventually inundating Waikiki’s dense thicket of roads, hotels, restaurants, shopping malls and condo towers. At high tides, water already sloshes out of some storm drains and pools in below-ground parking garages. If no action is taken, 6 feet of sea level rise would put Waikiki permanently under water.

As a result, some in Honolulu are envisioning far more radical solutions than groins — hollowing out the first few floors of buildings, for example; creating a Venetian-style canal system; or turning Waikiki back into the wetlands it once was. These ideas, if implemented, seek to save Hawaii’s most popular attraction, located on the island of Oahu, by totally reimagining it. They also steer right into some of the thorniest questions cities face today as they try to plan for costly realities that lie years, not just decades, ahead.

Virtually no one here in this deep-blue state denies the serious risk climate change poses to the islands, and there is widespread acknowledgement about the need to the preserve the $7 billion in economic activity that Waikiki generates annually. Yet, little agreement exists about what this future adaptation should look like and who will pay for it. The resulting battles — playing out not between the political left and right, but among city and state officials, environmentalists, hotels, landowners and locals — foreshadows a new phase in the climate debate: No longer are coastal cities arguing about whether warming poses a monumental threat, but about the best way to respond.

In Waikiki, Eversole’s plans have faced resistance from community members who fear that dumping more sand on the beach and building more hardened structures in the water will benefit hotels and developers with beachfront property at the expense of Waikiki’s famed surf breaks and natural beauty. These and other advocates for bolder, longer-term solutions like a more natural shoreline and adapted wetlands are facing off against hotel owners, politicians and others whose agendas have far shorter time horizons.

'We have to figure out what to do about it'

“It used to be, ‘Oh, OK, we’ll think about it later,’” said State Sen. Sharon Moriwaki, from her office in the Capitol building here, still largely deserted during the pandemic. “But now everyone knows that the science says you’re going to be underwater, and we have to figure out what to do about.” With nobody else stepping up to take action, last year Moriwaki assembled a working group, including Eversole, to design a comprehensive adaptation plan for Waikiki over the next two years that could serve as a model for other areas. This month, Moriwaki submitted legislation that, if passed, would provide $800,000 for the state to create the plan, which would then get implemented by the City and County of Honolulu.

Getting that money is likely to be the easy part. Those with a say and a stake in what happens to Waikiki include officials within the state government, which controls the beach and nearshore waters; leaders from the joint city-county government, which has jurisdiction over everything inland of the shoreline; the powerful tourism industry, including many hotels owned by companies outside the state; plus, Waikiki’s 30,000 residents. At this point, city and state officials have vowed to work together and solicit input from the community. But scientists and activists worry they won’t move quickly enough to make difficult decisions, while the debate over how to respond — short-term engineering fixes versus long-term adaptive measures, containing nature versus working with it — only festers.

Moriwaki acknowledges her team is still at the starting line. “There’s a lot of hands in the pot, but so far the pot isn’t cooking,” she says. “But at least now there’s interest. Before there wasn’t even that.”

For centuries, Waikiki was synonymous with water. With a name meaning “place of spouting water,” the area was fed by a dozen streams running down from the Ko’olau mountains to the northeast of Honolulu and into the ocean. In the 15th century, Native Hawaiians used this patchwork of wetlands to develop a productive agricultural system, growing flood-adapted crops like taro and raising fish in large stone-walled ponds. Later, Chinese and Japanese sugar cane and pineapple plantation workers used some of the land to plant rice and raise ducks. At the shoreline, generations of Hawaiian royals had their residences, and everybody — royalty, commoners, men, women, children — came to surf the waves, with both canoes and long, heavy wooden boards. Called “wave-sliding,” or he’e nalu, the pastime was about celebrating and connecting with the ocean.

The area’s transformation into a commercial center began around the turn of the 20th century, shortly after Hawaii became a U.S. territory. In 1906, Lucius Pinkham, a businessman from Massachusetts who became president of Hawaii’s Board of Health, concluded that Waikiki’s drainage and mosquito issues were “deleterious to public health.” In a letter to the rest of the board, he argued that the population of impoverished Hawaiian, Chinese and Japanese farmers wasn’t the best option for the area, describing them as “a class of population that limited means force onto undesirable and unsanitary land.” Instead, he wrote, Waikiki needed a population like the one that had emerged in Los Angeles and other Southern California towns — people “of private fortune, who seek an agreeable climate and surroundings, and who expend large, already-acquired incomes.” In Pinkham’s view, these wealthier (and, yes, whiter) people from the mainland would allow Waikiki to become an “absolutely sanitary, beautiful and unique district.”

After President Woodrow Wilson appointed Pinkham as Hawaii’s territorial governor in 1913, Pinkham used a preexisting law to allow the Board of Health to declare any parcel of land unsanitary and then place a lien on it if the owner was unable to afford the necessary improvements. In a move that today rings with exploitation and discrimination, Pinkham then started auctioning off properties. To create stable real estate on which to build homes, he initiated plans for the developer Walter Dillingham to build a 2-mile canal. Completed in 1927, the Ala Wai Canal, which serves as Waikiki’s northern border, drained the wetlands and provided dredge material to fill in the swamps. It also simplified the watershed by redirecting streams from higher elevations into one major input that fed into the ocean at one end.

With plenty of solid land for development, homes quickly began popping up. When passenger air travel to Honolulu was made widely available in the post-World War II era, high-rise hotels to house Waikiki’s growing numbers of visitors became a fixture of the skyline. Amid these changes, Waikiki’s surfing culture endured and was exported to the rest of the world by gold medal Olympic swimmer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku, who grew up in Waikiki and mentored a generation of “beach boys.”

One of them was the late George Downing, a pioneer in big-wave surfing and the design of surfboards. “My dad literally grew up on this beach and spent much of his life working to protect Mamala Bay,” said his son Keone on a recent afternoon, a view of Diamond Head Crater rising in the background.

The groins & the surf breaks

A tanned 68-year-old and former professional surfer, Downing has become one of Waikiki’s most prominent voices arguing that the state’s current climate adaptation efforts favor hotels, tourists and wealthy property owners, not the natural environment once cultivated by Native Hawaiians and beloved by locals. In Downing’s view, Eversole’s plans to build four new T-shaped groins in front of the Sheraton, Halekulani and Outrigger hotels threatens several of Waikiki’s most popular surf breaks; when waves hit the groins, energy refracts back out into the ocean, leading to smaller, weaker breaks.

He claims that after the Royal Hawaiian groin was built 18 months ago, it turned the nearby Canoes break into a “mush burger.” Downing believes that instead of “throwing rocks in the water” to hold in sand and slow erosion, the state and Special Improvement District Association should replenish the beach with regular, small-scale pumping of sand back to shore as it naturally washes out in the waves, perhaps monthly and at night, when it won’t be intrusive.

“I really like Dolan — he has a conscience,” says Downing, who runs Save Our Surf, a small but well-connected advocacy organization he took over after his father’s death. “[But] if he’s successful in building these groins, the hotels are the only ones that will benefit, creating a higher value for their properties when they get ready to sell.” (Eversole, himself a surfer, readily admits Waikiki’s visitor destinations are a priority — “We can’t kill the golden goose,” he says — and while he has heard concerns about the Canoes break generating shorter rides, he considers such changes subtle and short term.)

On Maui, a similar proposal for beach widening by the State of Hawaii and the hotel industry also is encountering opposition from community members, many of them Native Hawaiians who worry about long-term impacts on coral reefs and fishing, as well as short-term disruptions to canoe racing. Several people have promised to “stand in front of bulldozers” to stop the project, arguing that hotels and condos should start making plans to retreat inland.

For now, Downing isn’t calling for a similar exodus in Waikiki, in part because the hotels have nowhere to go; slightly smaller than Maui, Oahu houses more than six times its population, a total of just over 1 million people, 350,000 of them in Honolulu. Longer-term, though, he wants to see policymakers and industry leaders adopt strategies that seek to work with the ocean, rather than hold it back.

“Just because we’ve screwed up Waikiki with all these man-made structures doesn’t mean we have to keep screwing it up,” says Downing, a former land board member at the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources and current member of the Hawaii Tourism Authority board, who says he has the ear of Gov. David Ige. Eversole says the state has received north of 150 negative comments about the upcoming groin project from community members and various groups. The influential Surfrider Foundation, for example, said in its comments that because T-head groins have “significant impacts” on ecosystems, marine life and surf breaks, it prefers “less intrusive” designs.

When I met up with Downing last month, he was eager for me to see a recent project he considered to be a lost opportunity. On Waikiki’s quieter Diamond Head side, past the strip of oceanfront hotels and along a pedestrian path abutting a public park, we stood on a newly installed platform of concrete pavers. Part of a walled structure originally built as public baths in the early 1900s, this rectangular extension from the walkway had been damaged by decades of pummeling from the waves.

“This was a perfect place to experiment with what happens when you let the water go where it wants to,” Downing said. “You’ve got no hotels or buildings in the way. Take out the wall and let the water bring the sand and the beach up into the park.” Instead, the City and County of Honolulu hired a contractor to rebuild the walls, place additional sand inside and lay the concrete pavers on top, creating the visual effect of a short, sloping sidewalk to nowhere.

A person with knowledge of the project said there were several roadblocks preventing serious consideration of a beach cove. The city, this person said, didn’t want to lose its investment in the rebuilt pedestrian promenade on top of the wall, while the Kapiolani Park Preservation Society, which protects the large public park nearby, does not want to see any park land lost, the group’s president told me. The city’s Department of Design and Construction did not respond to requests to comment for this article.

For Downing, this so-called Queen’s Beach project — in which multiple entities clung to the status quo instead of looking at the bigger picture — is the kind of business-as-usual, quick-fix solution he believes is all too common in Hawaii and that has left the entire stretch of Waikiki Beach pockmarked with crumbling pieces of groins, walls, semi-exposed drainage pipes, century-old foundations and useless stairs — all eyesores on this once untouched land. “Nothing ever gets removed, and there’s no long-term vision,” he says. “We’ve got to start doing things differently.”

THERE IS QUITE A BIT MORE TO THIS ARTICLE – CAN READ THE LOT IN THE LINK BELOW

- AUTHOR: MELANIE WALKER

- SOURCE: POLITICO

Please choose your region

Australia | US / Rest of the World(Changing your region, will clear your cart)